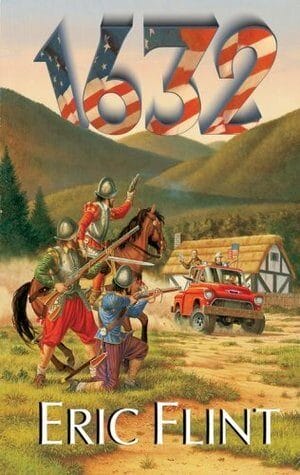

Eric Flint’s 1632 really kicks off the story when the mining town of Grantville in West Virginia gets teleported to Thuringia in central Germany. Not only are they teleported to an entirely different continent, but the town is also sent back in time and culture from modern-day America in the year 2000 to 17th century Europe.

And if those weren’t bad enough for the inhabitants of Grantville, they’re now in the middle of the long and bloody Thirty Years’ War. The time travel element in the novel promises interesting dynamics between the Americans and the Europeans, especially with their differences in technological advancements and outlook on the world, leading to major changes in historical events of the period.

Tech Reinvention

As far as the technological affair is concerned, the novel introduces its first surprising twist by letting the people of Grantville keep their level of technology intact. At this point of story development, the simple take would be that the Americans already are at a significant advantage in the war because they have plenty going for them. Everything in Grantville, including their modern weapons, ammunition, libraries, and power plant, are coming along in the time travel journey. There are even doctors and a veteran Marine in town, so at least the Americans would join the battle with some preparations.

1632 doesn’t just give you the image of a small yet determined force of modern Americans outgunning the enemies. The novel offers a fascinating take on that unusual circumstance with a much more careful approach to storytelling. Americans wouldn’t blindly rush to the battlefields; instead, their initial decision – pertaining to the inevitability of direct involvement in the war – is to bring down the 20th century technological advantage to Industrial Revolution level. In fact, some of the more interesting parts of the novel concern the way the Americans set up their equipment for the era. They never have to invent new technologies, but only re-invent things that have already existed in their actual timeline. Thanks to their industrial equipment and collective knowledge, it’s challenging, but far from impossible.

It sounds silly, but makes sense from the character’ perspectives. Maintaining a level of technology too advanced for the society at that period will only make everything too difficult to sustain. At least with Industrial Revolution era devices, the Americans and would-be allies can rebuild, recreate, and repair wartime machinery using the available resources and infrastructure. And since the Industrial Revolution era is still a full century ahead of whatever the Europeans have in the mid-1600s, the Americans remain at an unfair advantage.

The Unimportance of Time Travel Elements

Now, let’s talk about time travel. The story in 1632 can only happen because the people of Grantville, in the year 2000, are transported back to 17th century Europe. The plot moves on as if everyone in Grantville simply accepts the new reality and is ready to deal with it, no question asked. It’s odd that the story skips the talk about time travel mechanics, but the glaring omission actually serves the novel well, for some good reasons.

The concept of time travel involves something or someone moving from one specific time period to another. The destination time period can be the past or the future, without the time traveler having to experience life in the intervening periods. For example, if in the year 2024 you take time travel to the future world of the year 2100, the journey bypasses (from your perspective) every single detail that happens between the present-day and the destination. The result is that you arrive in 2100, but you’re not 76 years older than you are today.

Time travel has been a common plot device in sci-fi since the late 19th century, and many stories attempt to explain such a journey in a way that makes it sound like a scientific plausibility; they want to present a story that makes sense. Even if traveling to the past is possible, it would introduce paradoxes related to casualty that would render the journey incomprehensible.

The grandfather paradox is a common hypothesis to dispute the credibility of time travel (to the past) stories. The paradox throws a simple yet rock-solid argument: if you travel back in time to kill a person, and that the person turned out to be your great-great-grandfather, you cannot possibly exist to make the time travel. The main point is, you cannot interfere with the past because it will inevitably change the course of history and your own existence in the future. Here is another example: you travel to the past to prevent World War II from happening, and you succeed. However, if there had been no WWII in the past, well then there wouldn’t be a future where you needed to travel to the past to begin with. The inconsistency in the story is too great to ignore.

Eric Flint’s 1632 is smart to avoid the discussion at all. Time travel happens, and that’s about it.

We think technological innovation, or rather the way the Americans undergo the transformation from 21st century convenience into the level commonly observed during the Industrial Revolution era, is one of the most highlight-worthy parts of the novel. The time travel mechanics have a much lesser degree of importance in the novel, but this isn’t entirely a bad idea from a storytelling perspective. As mentioned above, the time travel mechanics can be quite complicated and impede the plot progression if the author focuses too much on it.

Do you think a group of Americans with their 21st century technology can become a superpower in 17th century Europe? Can you mention any lesser-known technological inventions in the 17th century? We’d love to hear from you.

Other Things You Might Want to Know

Some popular novels from the 17th century (not all are alternate history):

- Don Quixote by Miguel Cervantes (two parts, 1605 and 1615)

- New Atlantis by Sir Francis Bacon (1626)

- El Buscon by Francisco Quevedo (1626)

- The Man in the Moone by Francis Godwin (1638)

- The Other World: Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon by Cyrano de Bergerac (1657)

- The London Jilt; Or, the Politick Whore by Anonymous (circa 1660)

- The Blazing World by Margaret Cavendish (1666)

- La Princesse de Cleves by Madame de La Fayette (1678)

- The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyon (1687)

- Oroonoko: or, the Royal Slave by Aphra Behn (1688)

Historical fiction novels to read:

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead (2016)

- All the Broken Places by John Boyne (2022)

- When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka (2002)

- Our Lady of the Nile by Scholastique Mukasonga (2012)

- The Lotus and the Storm by Lan Cao (2014)

- Black Rain by Masuji Ibuse (1965)

- Emergency by Daisy Hildyard (2022)

- Caleb’s Crossing by Geraldine Brooks (2012)

War fiction books:

- Red Army: A Novel of Tomorrow’s War by Ralph Peters (1989)

- All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque (1929)

- Invasion by Eric L. Harry (2000)

- Red Storm Rising by Tom Clancy and Larry Bond (1986)

- Ghost Fleet by P. W. Singer and August Cole (2015)

- The Great Pacific War by Hector Charles Bywater (1925)

- The Iliad by Homer (eighth century BC)

- Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card (1985)

- Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein (1959)

- The Forever War by Joe Haldeman (1974)

Check out other articles by month: