Of all the sci-fi horror films 1979 brought out of Hollywood, nothing triumphed Ridley Scott’s Alien; some would argue that it remains the best the genre has given us so far. But somewhat stowed away in a bright corner of streaming services, there’s one space horror film titled “The Black Hole” waiting to be rediscovered. And it’s not just another space horror featuring extraterrestrial abomination equipped with the power of acidic saliva and horrifying body transformation, mainly because it belongs to Disney.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, Disney was heavily occupied with plenty of busy brainstorming sessions to match the enormous success of the original Star Wars, released in 1977. But being Disney, it couldn’t just make something action-packed with a lot of violence and murders–whatever it wanted to make, it still had to be “family friendly” as always. Even if they wanted to push the boundaries with a more mature and scary content, everything needed to be within the parameters of entertainment for all ages. This gave us films like Tron (1982), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983), and The Black Cauldron (1984). Before all of those, however, there was The Black Hole. While not being celebrated because of its exciting storylines or actions, it deserves all the praise in the world for its use of creative, practical visual effects.

First things first, The Black Hole isn’t exactly a horror film in the traditional sense of how the term is typically defined. It has no scary monsters or extraterrestrial species threatening the lives of a spaceship crew. That said, the film unmistakably exudes a peculiar eeriness and a creepy enough visual that no one will blame you for taking it as a horror feature.

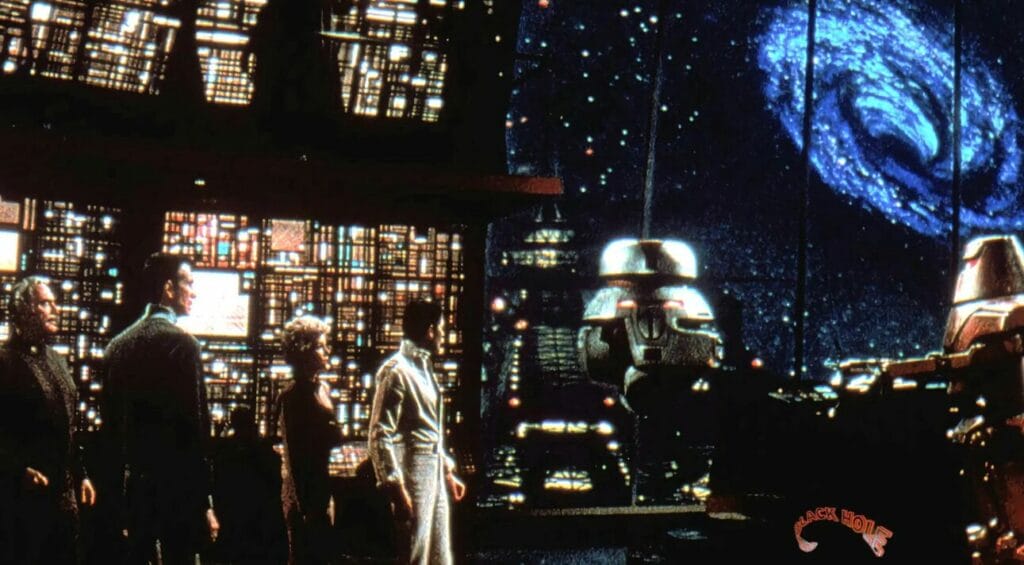

It tells the story of the crew of the explorer craft, U.S.S. Palomino, during the journey home following a fruitless space exploration to search for signs of extraterrestrial life. Somewhere along the way, they encounter the supposedly long-lost U.S.S. Cygnus, floating near a black hole. The spaceship (Cygnus) is controlled by Dr. Reinhardt and his robotic assistant called Maximilian. The crew of the Palomino simply can’t believe what they see, considering the fact that nothing should be able to come that close to a black hole and remain intact. This sense of wonder soon turns into a horror when it’s unveiled that Dr. Reinhardt plans to lobotomize everyone aboard the Palomino and turn them into his pawns, before taking them to fly through the black hole. A meteorite shower suddenly strikes, plunging the remaining survivors into a dimension no one has gone before.

Back in the day, Disney was adamant that the visual effects be nothing short of wonderful, to where they brought Peter Ellenshaw back from a 10-year retirement to lead the team. He produced 150 matte paintings and 550 effect shorts for the movie–massive numbers at the time. As a matter of fact, the visual effects in The Black Hole established a new standard in movie production technique, using one of the most intricate matte shots ever devised in the entire history of filmmaking. Some say the Matte Scan camera invented for The Black Hole was even more revolutionary than the Dykstraflex camera used in Star Wars.

For every shot of a black hole seen from the perspective of a crew through a window of a spaceship, that’s a special/visual effect made from a plate of a whirlpool inside a Plexiglass water tank with some dyes for coloring.

Art Cruickshank, the Director of Miniature Effects Photography of The Black Hole, gave several good examples of how the special effects for the films were produced, in an interview with Fantastic Films and Other Imaginative Media. He said that the film involved more miniatures than any film or show he had worked on before. There must have been somewhere between 150 and 175 cuts with miniatures, and often involving overlap with Ellenshaw’s matte shots. For instance, many times when the Palomino was seen approaching the Cygnus, the people inside the former were looking at the latter through a window; the background for the blue screen was, in fact, a miniature. The technique was used extensively throughout the film.

As for the Cygnus itself, the film used a 1/16th-inch scale model, meaning that every inch of the model represented 16 feet of the ship as it was shown on screen. There was also a one quarter inch scale model used for sections of the Cygnus meant to be blown apart. Most of the models were built in those two scales. There were several shots involving characters on an air tube outside the Cygnus; especially for the scene, the visual effects team used the 1/16th-inch scale for the U.S.S. Cygnus and a half-inch scale for the air tube, which turned out to be around four inches. The air tube model needed to be that large because the camera lens had to go through, creating the impression that the characters–while riding a true 1:1 scale model–were accelerating at a blistering pace.

A few models were built mainly for photography purposes. The film required an image of the Cygnus right side up, and another upside down; both were 1/16-inch scale models. Everything else was a quarter-inch scale and in an upright position because the film only needed to show the dining room and control tower. The U.S.S. Palomino was also made in two models of different scales: a quarter inch and 1/16th inch. The former was around two feet, whereas the latter came up at just six inches.

Apart from The Black Hole, other films known for the extensive use of practical effects are The Fly (1986), with every stage of molecular decay and decimation befalling Seth Brundle was made entirely with prosthetic makeup and puppet; Scanners (1981), famous for the use of head prop–filled with leftover burgers and whatever bits were lying around in the studio–getting shot with a 12-gauge shotgun to create the iconic head explosion scene; and of course The Thing (1982) where the creature effects were made using many things including prosthetics, hydraulics, puppetry, foam latex, and stop-motion animation.

We think practical effects still have their place in modern filmmaking, especially in movies that involve a lot of body/biological horrors. Although the much more advanced CGI technologies have replaced the need for its more conventional counterpart, prosthetics sometimes just appear more convincing on screen, if used properly. Even modern films like Interstellar still used miniatures for the spaceship and the old-school set-building rather than CGI green screen.

Are there specific practical effects that make a film looks bad? Can you actually notice the difference between practical effects and CGI while watching a film? We’d love to hear from you.

Other Things You Might Want to Know

Can you actually categorize The Black Hole as sci-fi horror?

It’s questionable at best, but you can kind of think of it as a light, family-friendly sci-fi horror. Most of the scary contents are from the creepy-looking robots, the unsettling tone, the rather dark ending, and the crew’s psychological disturbance.

Recommended sci-fi horror books:

- The Rediscovery of Man by Cordwainer Smith

- Blood Music by Greg Bear

- Bloodchild and Other Stories by Octavia Butler

- Under the Skin by Michel Faber

- Remina by Junji Ito

Some of the scariest movies Disney made:

- Bambi (1942)

- Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983)

- The Watcher in the Woods (1980)

- The Black Cauldron (1985)

- Return to Oz (1985)

- Escape to Witch Mountain (1975)

- The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949)